Novel perspectives, emotional proximity, and working out what we take for granted

Thinking about what digital is good at.

Through the work we’re doing on the Venues of the Future R&D project we’ve been trying to trace the common threads and themes that are present in most of the more successful digital cultural experiences.

I’ve returned to some of the landscape mapping work I did during the pandemic. It was interesting to see what bubbled up in amongst all the experimentation, what worked, and what failed.

I revisited this article from the New Yorker alongside the 2012 documentary, Leviathan.

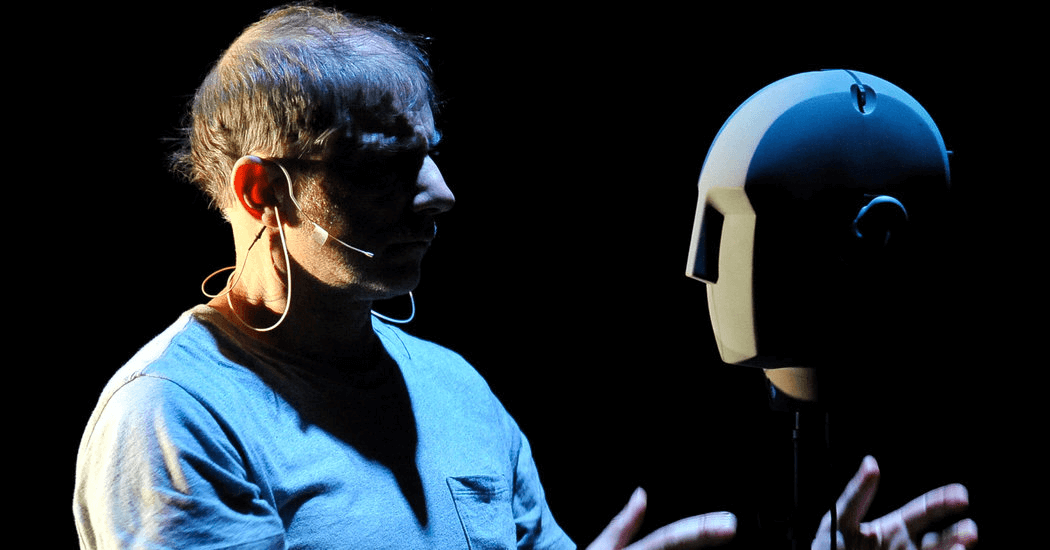

I thought about the Royal Court’s performances of My White Best Friend (and Other Letters Left Unsaid) over Zoom, Complicite’s binaural audio production of The Encounter, the Royal Opera House’s Current Rising, Darkfield Radio, Spike Lee’s film of David Byrne’s American Utopia, and these one-on-one performances from Opera North, and Bon Iver’s Justin Vernon.

One of the common themes that emerges is the way in which digital approaches seem most interesting and successful when they are not simply used to copy.

A facsimile of something that is happening in its ‘true’ form in a physical space, with a physical audience will always feel hollow, forgettable and disposable.

Instead when the digital experience is considered as something in and of itself, something special can start to take root.

Research through, and immediately after, the pandemic (in the UK, North America, and Australia) also showed that this sort of ‘born digital’ experience, and - perhaps surprisingly - digitally-delivered education programmes, was the work that audiences were most comfortable attaching an actual monetary value to.

Exploring what makes good work is a big part of the research we’re doing through Venues of the Future, but in revisiting the work above and reflecting on recent conversations there are a couple of immediately commons themes in particular that I am interested in highlighting.

Novel perspectives

Digital is uniquely placed to remove barriers and to present a point of view that would otherwise be impossible to achieve or enjoy through traditional forms of cultural engagement.

Whether that is a camera or microphone placed somewhere that the human eye or ear would never be able to reach (as in the case of Leviathan mentioned above where cameras and microphones are attached to dangerous and/or completely submerged fishing equipment on a deep sea trawler), or the ability to be part of an intimate one-on-one performance (the Opera North and Bon Iver examples).

Digital can play with scale and perspective in a completely unique way, as in the case of the mixed-reality experience of Current Rising.

Emotional proximity

The second is perhaps an extension of the first. The the ability of digital to, as Annette Mees puts it, ‘zoom in, in every way’.

By this she means, yes, the ability for digital to take us far closer than we would be able to get through most traditional modes of culture.

But also, through doing this, digital can unlock a unique feeling of connection, engagement, or even confrontation.

The Darkfield Radio and Complicite examples shared above use binaural audio to immerse and confront the listener, and in doing so deeply connect them with the story they’re telling.

In Spike Lee’s film of David Byrne’s American Utopia show, the viewer is given a completely different experience to the people sat in the theatre. The authors of the stage show and the screen experience are different people, with different priorities, connecting with the audience in different ways.

And this brings me to a final thought.

Understanding what we take for granted

When a person is in a physical space, engaging with a cultural experience that is happening in a ‘physically co-present’ way in that same space there are a huge number of things that are taken for granted.

In a digital space these things are absent and have to be specifically addressed and proactively ‘rebuilt’ or ‘inserted’ into that digital experience.

Collective effervescence (the sense of energy and harmony people feel when they come together in a group around a shared purpose) is something that more naturally occurs when humans gather together in the same physical spaces.

It is more difficult (but not impossible) for this to occur in digital experiences but requires a high degree of effort and intention for this (or something similar) to be present.

As we’ve realised over the past few years of increased remote working and remote…everything, we take so much for granted with so much of our interpersonal interactions.

When we are replicating those structures in digital spaces we have to be thoughtful, proactive, and intentional about how we want them to exist, we are building everything from the ground up.

This last point is, I think, what explains much of the ‘emptiness’ that is often present in many of the less successful digital cultural experiences.

We need to think harder about the things that we take for granted when visitors or audiences enter our physical spaces.

As Matt Locke said when I spoke to him for the Digital Works Podcast, “everything has a format, even if it's just that some of that has become so ingrained into the delivery of culture that you don't think of them as format”.

If we can develop a clearer, shared understanding of the intangible elements that underpin our ‘real life’ cultural forms and experiences then we will be better placed to imagine how they might exist in digital spaces in the most successful, satisfying, impactful way.

You can read more about the Venues of the Future project (in Dutch) on the Innovatie Labs website.